I am a domestic violence survivor. You can’t tell by looking at me, and you never could. I didn’t have black eyes or bruises. I never went to the hospital and claimed I fell down the stairs. I am a woman with a disability, and I was abused by my former partner, another woman.

Domestic violence affects millions of women and men with disabilities. In fact, women with disabilities are twice as likely to be victims of domestic violence as non-disabled women. That means half of all women with disabilities will experience domestic violence in our lifetimes. We also tend to stay in abusive relationships longer, and have difficulty accessing the services we need to escape from an abuser. The disability community talks about topics like accessibility, employment and health care, but too often we ignore this issue that affects so many of us. My story illustrates how easily a person with a disability can become a victim of domestic violence. So for Domestic Violence Awareness Month, I’m speaking out. Because it’s time we end the silence.

I have cerebral palsy, a condition caused by brain damage at birth. I have limited use of my arms and legs, and use a power wheelchair. Although I need a lot of physical help with daily tasks, I have always been a very independent person. I grew up with loving parents who encouraged me to pursue my dreams, graduated from Stanford University and have lived in my own home and worked at various writing and Internet-related jobs for my entire adult life. I am a strong woman who has fought against inaccessibility and discrimination. I would read stories about women who were abused and I couldn’t understand why they would stay. I would never put up with being treated that way, I thought. That could never happen to me. I was wrong.

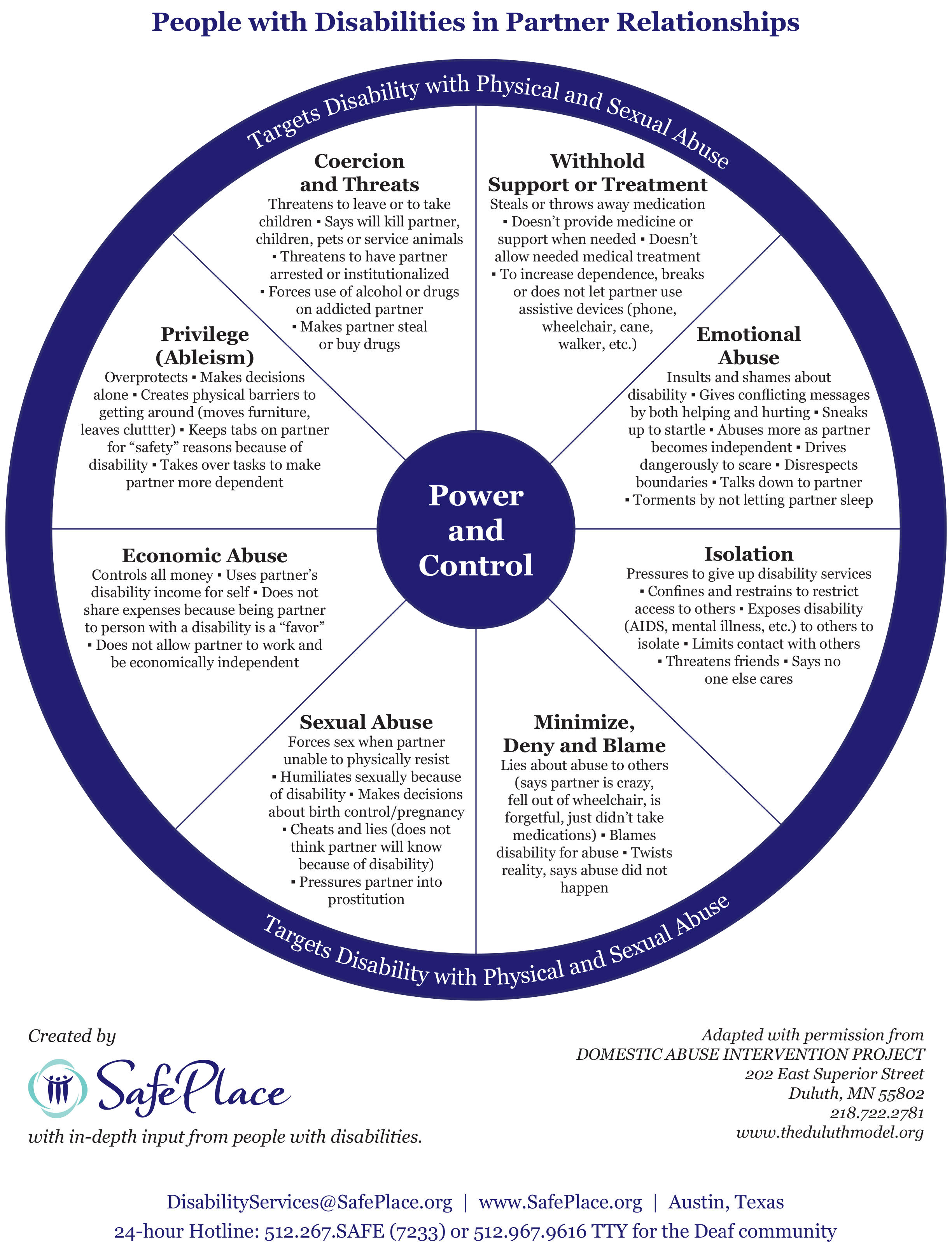

Abuse can look different when it happens to people with disabilities. Our abusers may hit us, but often, they don’t have to. They have far more insidious tactics for coercive control and manipulation. Abusers may make their victim feel guilty for having a disability, exploiting fears many of us have about being a burden. We may stay because we believe no one else would love someone like us, that we can’t do any better. My abuser broke down my self-esteem by gaslighting me and making me believe my body and my life were too difficult for others to deal with. She used this supposed difficulty as an excuse to keep me stuck at home most of the time, where I became depressed and gained weight. Then she used those changes to humiliate and body-shame me, saying things like “you’re too fat to travel.” I was a size 18, but I hated my body so much by then, I believed her.

Many people with disabilities depend on their abusers for physical assistance. Sometimes the abuser may encourage this as a means of gaining more control, pushing away other caregivers to isolate the victim. If the abuser provides personal care, they may berate us while “caring” for us or withhold essential care as a form of punishment. Even though my abuser only assisted me for an hour every evening, and I had paid personal care attendants for the majority of my care as well as all our housework, she would complain that helping me was “too much” for her, that it changed how she saw me and made me not seem sexy anymore. She would humiliate me and threaten to leave me stranded on the toilet if I didn’t say or do what she wanted. Some nights I would pee my pants because I couldn’t face the abuse and was trying to hold it all night until I had a caregiver to help me in the morning. Of course that made her even more angry. But when I suggested hiring someone to help at night, she refused to allow it, saying that would interfere with her peaceful, quiet evening. By then my self-esteem was so destroyed, I couldn’t even see that wasn’t her choice to make.

Abusers can use access to communication devices as a means of controlling people with disabilities. Simply placing a mobile device or AAC device on a high shelf could be enough to take away someone’s access to family and friends. My abuser repeatedly threatened to break my computer or headset when I was talking to friends online, which would have cut me off from my only real source of emotional support at that time.

Financial abuse is also all too common, and can range from outright theft to manipulation. If the person with the disability has money, abusers can say things like, “I can’t work because I’m caring for you, [even if it’s not true] so you should buy me this car.” My abuser refused to get a job or help with the online business I was running at the time, but would spend thousands of dollars I’ve never been able to account for. By the time I escaped from the relationship, I had gone from financial security to having to go on disability benefits and Medicaid. If the person with a disability doesn’t have money, a more common scenario, they may be financially dependent on their abuser, and vulnerable to threats of losing health care, food and a place to live.

Need a text description of the power and control wheel? Click here.

When an abuser uses subtle psychological tactics, engaging in a pattern of coercive control, abuse can be harder to recognize. I always thought domestic violence was when someone hits or sexually assaults you. If my partner had done either of those things, I would have known it was abuse and I believe I would have left the relationship sooner — though I can’t know for sure, and I don’t judge anyone who stayed in those circumstances. I believe “smart” abusers often know your line in the sand and find other ways to control you that you may not even be aware of until it’s too late. I didn’t recognize the constant belittling as emotional abuse, or see how the life I’d worked so hard to build was being slowly destroyed. I didn’t realize how much damage gaslighting could cause until I was a shadow of my former self, meek and apologizing for my very existence. But eventually, abusers can lose control. My abuser’s rage started coming out when others were around; her threats to hurt me and my possessions increased. She came close to hitting me a few times, so close that I couldn’t deny it was going to happen, and soon. She had been abusing me long before that, but I couldn’t acknowledge it until her behavior became more obvious.

My friends, the ones she didn’t want me talking to on the computer, saved my life. They helped me realize the way I was being treated wasn’t right. One was a domestic violence survivor herself. She sometimes overheard my partner’s comments and behavior when we chatted on Skype, and told me her first ex-husband had said many of the same things. Another friend encouraged me to start going out again, to ask my assistants to take me more places, which they were happy to do. Then I got a glimpse of freedom. My abuser had to spend several weeks out-of-state helping a relative recover from a sudden illness. The day she left, I felt as if an enormous weight was lifted from my shoulders. I started remembering who I used to be, who I still was deep inside. Then I did the wildest and most wonderful thing I’ve ever done. With almost no planning in advance, I took a cross-country road trip from California to New York City, meeting my online friends who’d been so supportive. And along the way, I found myself again. I realized I had to break free. But it wouldn’t be easy.

When people with disabilities try to escape from an abusive situation, we face challenges others would not. Although I’ve primarily been discussing intimate partner violence, an abuser may also be a parent, sibling, other relative, personal care attendant or staff member at a nursing facility. Many people with disabilities are physically and/or financially dependent on their abusers, and need support in multiple areas to extricate themselves. When a victim reports abuse, it may get swept under the rug or dismissed as the actions of a “frustrated” or overwhelmed caregiver. Some victims may struggle to describe abuse due to communication difficulties or intellectual disabilities.

Even if the victim is taken seriously, getting to safety is often difficult. Many domestic violence organizations do not have wheelchair accessible shelters, and accessible permanent housing, especially affordable housing, is scarce in virtually every city in the United States. Some women may stay in a relationship because they fear their spouse will try to get custody of children by claiming they can’t care for them due to their disability. I have friends who were denied primary custody based on a disability, even when there was a documented history of domestic violence by the other parent.

I was fortunate that my house and bank accounts were only in my name, but I still had to fight to keep what was left. Domestic violence victims with disabilities can struggle to prevail in court proceedings against abusers, because attorneys and judges often don’t understand that abuse can look different for people like us. During the divorce, my abuser refused to leave and tried to drag things out as long as possible so she could continue to sponge off me. I was terrified every moment I was alone in the house with her. Even though I detailed all of her abusive actions, my attorney did not have a good understanding of what constitutes abuse of a person with a disability, so she didn’t believe my abuser could be forced to leave immediately. It took the abuser stealing my credit card and making $1200 in unauthorized charges for both attorneys — mine and hers — to see what an exploitative person she was. A few horrible days later, it was all over. I had my life back.

That was six years ago. Since then I’ve worked hard to heal and rebuild my self-esteem. I still struggle with blaming myself for “letting the abuse go on” for as long as it did. Much as I want to forget all the terrible memories, I have found value in remembering. I think of how trapped I felt, but wonder why didn’t I break free? The answer is there, both haunting me and bringing a kind of peace. I stayed because I’d been bullied into believing I was worthless. I stayed because someone slowly and systematically took away my power. I stayed because I live in a society where people with disabilities are often seen as less desirable and encouraged to “settle” for whoever will have us. I stayed because people with disabilities are often expected to be unconditionally grateful to those who help us, even if that help comes with a heavy dose of coercive control. I internalized those harmful messages even though I was a successful, determined woman who believed I could be and do anything, and my life up to that point had proved it was true. I was a victim of domestic violence, and it wasn’t my fault. And if it happened to me, it can happen to anyone.

If you have a disability and are currently experiencing domestic violence, or if you’re a survivor, please know you’re not alone. And although it may seem like a distant memory right now, you can find freedom and joy again. Today I have a nice house, a job I like and friends I love who love me in return. I enjoy shopping and restaurants and theatre, and I have a beautiful service dog by my side wherever I go. As for being too fat to travel? I’m now a travel blogger, chronicling my road trips around the USA to show others that they shouldn’t believe anyone’s toxic lies or let a disability stop them from living life to the fullest. I am open to finding a woman to spend my life with, but I will never again compromise who I am for someone else or tolerate abuse. I have emerged from the nightmare of abuse as a stronger person, with an unshakable belief that I deserve respect as a human being and I have something to give to the world. I am a domestic violence survivor, and I’m not ashamed to speak out. It’s time to end the silence.